27 October 2014

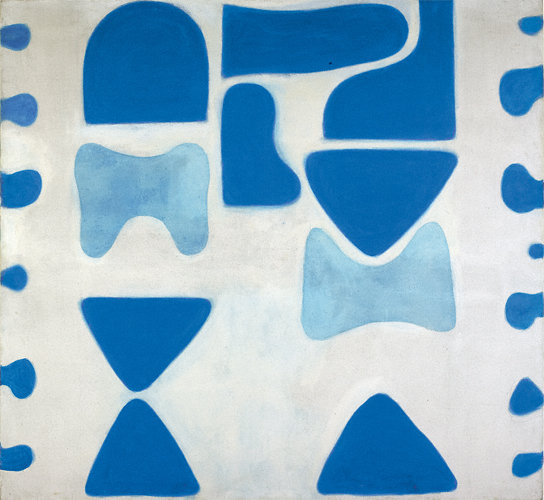

In November 1934, the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas moved from his home town of Swansea to London, sharing a room with his childhood friend, Alfred Janes. Thomas quickly became assimilated within Janes’ circle of friends, one of whom was William Scott (Janes, like Scott, was a student at the Royal Academy Schools). Before long, Janes, Thomas, Scott and Mervyn Levy (who had been at school with Thomas and was, by the early 1930s, a student at the Royal College of Art) were all sharing digs in Chelsea. Later, remembering this time, Scott described Thomas as ‘a poet living with painters’, with no need of a room of his own; ‘apparently a poet didn’t need one: he slept on the floors of his friends, using his trousers for a pillow.’

In histories of Thomas’s career, this period is of particular interest as it witnessed his arrival on the London literary scene – in December 1934 his first volume of poetry ’18 Poems’ was published. Perhaps what is not so well known is that, during this time spent in London, Thomas also experimented with pictorial creativity, even if in a pretty minor way. The incident – and indeed the period as a whole – was recalled some years later by Mervyn Levy in an article on Scott, in which he powerfully evoked a fascinating – and historic – moment in the lives of both William Scott and Dylan Thomas:

‘Standing with William Scott a few days ago outside No. 35 Edith Grove, Chelsea, the house where as art students we had shared for a while the same flat, I listened to the gentle voice of the painter, one of my oldest friends: “You remember, Levy?” I remembered. And that other house at No. 21 Coleherne Road where we had lived with Dylan Thomas in the early thirties. I was then a student at the Royal College, Scott at the Academy Schools. He still possesses a remarkable souvenir of those years. An early Academy painting of his, which even then displayed the same clarity of conception, the same essential purity and economy of means as that which distinguishes the latest of his works. The picture, now hanging in his Chelsea studio at Edith Terrace, a mere dream’s nip around the corner from that other house in Edith Grove, is based on a religious theme. Angels hovering around some rooftops. On this portion of the painting, one night, a tipsy Dylan was permitted to lay in the lines of some tiling. It must be the only pictorial expression of the poet’s genius in existence.’