William Scott: a painter of pots and pans…

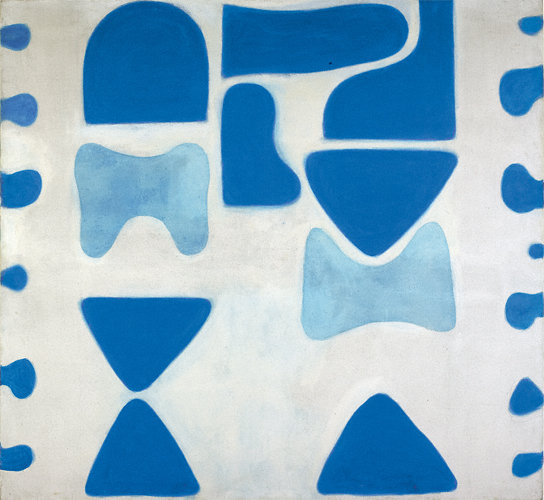

‘You’re the man who “does pots and pans”…’ was Tony Rothon’s opening line when he interviewed William Scott in 1974 (published that year in Studio International). Although a deliberately glib remark, the point was a valid one; four decades on from when Scott first started exhibiting, he continued to be best known for his still life paintings of kitchen objects – pots, pans, knives, bottles, jugs and bowls. Yet, despite the regularity with which they featured in his work, in themselves these objects held little interest for Scott. He chose them precisely because they were commonplace and mundane, their relative lack of meaning allowing him the freedom to focus on and exploit their formal qualities. ‘The subject of my painting,’ Scott explained to Rothon, ‘would appear to be the kitchen still life, but in point of fact…my subject is the division on canvas of spaces, and relating one space or one shape to another.’

Scott was not a fan of discussing his work. In his opinion, art was for looking at, not for talking about. Aside from the odd interview (such as that given to Rothon), written statement or lecture, it has hard to glean exactly how he viewed his own output and his development as an artist. An intriguing exception to this is a letter Scott wrote in 1952 to an unknown correspondent called ‘George’ in which he explained the genesis of the pictures of frying pans which he had begun painting in the post-war years:

‘About four years ago I painted a picture of a frying pan and a whole napkin. I had been interested in the work of Braque for a long time but I felt that it was dishonest to merely take as some people have done the guitar, the carafe and the French loaf. I felt that in painting my own familiar objects I might imbue them with a conviction characteristic of both myself and my race, if the guitar was to Braque his Madonna the frying pan could be my guitar, black was a colour I was fond of and I possessed at that moment a very black pan.’

Scott went on to explain that he had added other objects common to the kitchen into the mix – eggs, a toasting fork – while also experimenting with the shape and form of the pan and its handle.

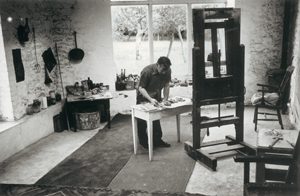

The more familiar these forms became, the more Scott moved away from reality, no longer concerned with verisimilitude. In photographs of his studio from the mid-1950s, the pans, forks, ladles and frying-baskets are seen hanging on the walls; no longer to be studied, they float like friendly ghosts. That said, another series of photographs – of still life arrangements of bowls, fruit, pans, eggs – suggests that Scott did later return to looking at these real still life elements as an aid to constructing his compositions.

The letter, the photographs and the objects themselves (all of which are in the William Scott Archive) has formed the basis for a new exhibition of William Scott’s work which opens at the Verey Gallery, Eton College on 10 November. The show – which brings together works in oil and on paper – will focus specifically on his still life practice, considering how Scott explored the theme over the course of his career. The show also invites the viewer to look beyond the subject matter and to reflect on Scott’s final words to ‘George’:

‘What I have said may lead you to think that I was mainly absorbed in the content but… my primary interest (the abstract relationship of form and colour in space) is a subject that does not lend itself well to expression in words.’

William Scott Form – Colour – Space opens at the Verey Gallery, Eton College on 10 November 2016 (closes 31 March 2017)

www.etoncollege.com